Did you know Fresno has a Chinatown?

As long as Fresno has existed in its colonized form, Chinese immigrants have been woven into its existence. Chinatown was born a child of segregation—resilient, dynamic, and adaptable. One hundred fifty years after its birth, remnants of several eras on the “other side of the tracks” are being pieced together by community members invested in hope, imagining a future anchored in the past.

The Cultural Heritage Center & Chinatown’s 11 Identified Cultures

The Cultural Heritage Center (CHC), located on Kern Street and China Alley, describes itself as “a hub for cultural exchange, education, and celebration.” According to their website, “We are cultivating understanding, appreciation, and respect for the rich history and traditions found within Fresno and the eleven-identified original cultures of Chinatown.”

Pheej Lauj (he/they), director of the CHC and a Fresno native who grew up with Downtown Fresno as their “playground on the weekends,” returned home in 2024 after completing a master’s degree in Utah.

“It’s so good to just have a job that allows me to learn more about my hometown and more about Fresno and Chinatown's history. There's a lot of beautiful stories,” Pheej said.

While the center itself is new, the work to uplift Chinatown and the many cultures within Fresno is not. Pheej highlighted the community members who have already “spent a lot of time, energy and heart” into gathering and preserving pieces of history paving the way for the center to bring them all under one roof.

“One thing that we're trying to do is pick up where those things are and provide opportunities for them to really kind of shine and to be able to share with the community,” Pheej said.

The community has also guided the CHC’s direction. Neighborhood residents, many who have lived in Chinatown for decades, often stop by the center to say hi.

“These are your community historians and business owners… (they) symbolize what Chinatown represents, which really is historic, longstanding, and kind of resilient businesses and communities,” Pheej said.

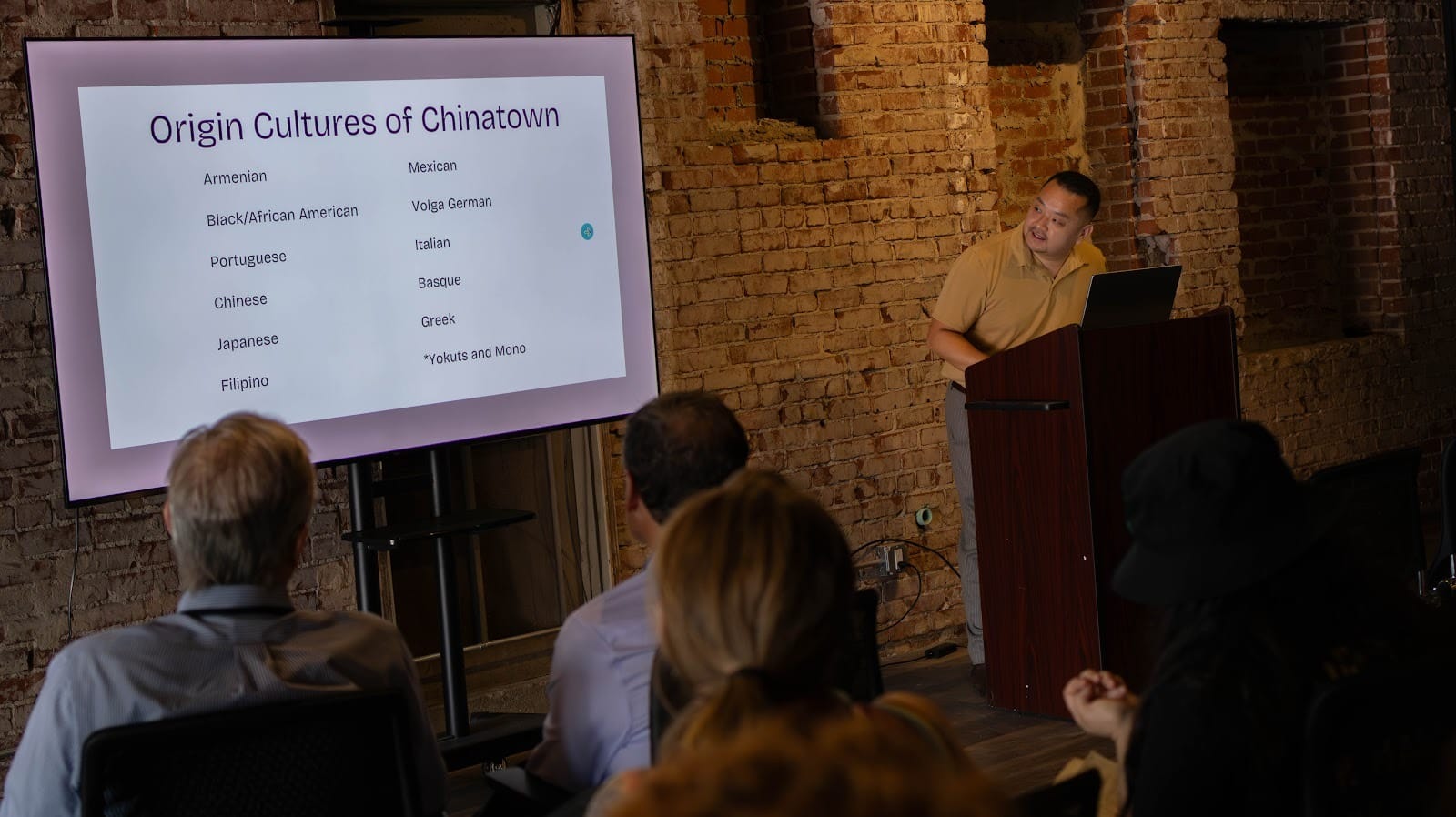

The 11 identified cultures whose history intersects with Chinatown are Chinese, Black/African American, Portuguese, Japanese, Filipino, Mexican, Volga German, Italian, Basque, and Greek.

While the cultures come from all over the world, their stories converge in the heart of California’s Central Valley.

“Fresno has these beautiful and amazing cross-cultural histories and legacies that we all are from and that we all can learn from…When I think about my family's war and immigration and kind of assimilation stories here, the themes of it aren't too different. And I think there's something very, very beautiful about that. It's a commonality across differences. There are so many ways this center could build with community. I'm looking forward to continuing to explore what that looks like as we get started,” Pheej said.

Note: The CHC is not to be confused with Chinatown Fresno. While the two work closely and there is some overlap in mission, they are two separate organizations with their own non-profit statuses. Chinatown Fresno is an organization dedicated to economic empowerment, neighborhood development, and cultural heritage. The CHC specifically focuses on uplifting cultures that have historically existed and currently exist within Fresno, but have been underrepresented, beginning in Chinatown, which predates Fresno’s formal recognition as a city.

Fresno’s History of Chinatown and Structural Inequities

In 1872, the Central Pacific Railroad Company laid tracks over Southern Yokuts territory and established Fresno Station, the center of what would become Fresno. Two years later, Fresno was voted the new county seat, succeeding Millerton (modern-day Millerton Lake bottom).

Many Chinese immigrants traveled from Fort Miller, where they had been forced to live by white businessmen, exchanging gold mining pans for pickaxes. Despite their integral role in the origin of the railroad town, racist policies similar to those in Millerton segregated the Chinese population to the area west of the newly constructed railroad line.

Fresno has repeated this pattern of pushing entire groups to the fringes of town, limiting upward mobility in a capitalist society that relies on intentional stratification. This systematic oppression has affected multiple ethnic groups over the city's 150 years and is visible today in the abandonment and destruction of historic buildings and the lingering traces of displaced communities.

White Supremacy Written into Policy

Social marginalization was reinforced by federal law as early as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Geary Act of 1892. Later city plans reflected these policies at the local level.

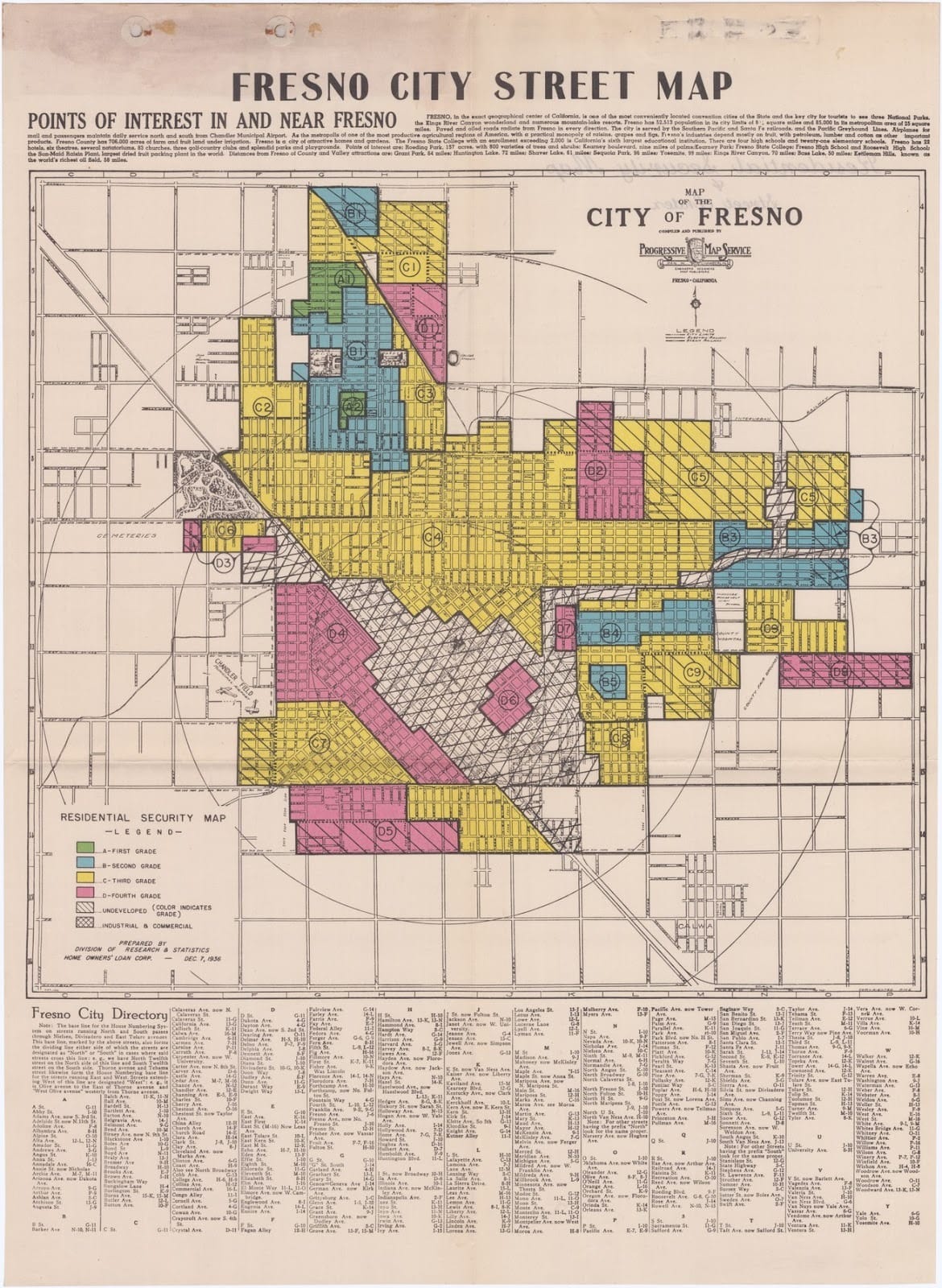

Author and social justice expert Nathan K. Hensley writes in Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, “Fresno's heavily racialized city plan took its current shape, then, in cycles: redlining in the late '30s; whites-only deeds in the '40s and after. In the 1950s, the main road running parallel to the Central Pacific tracks, Highway 99, was expanded into a multi-lane expressway, sealing hazardous elements from Fresno's white core and demolishing thriving mixed-race neighborhoods in the process.”

From the cool fullness of old growth trees down Van Ness to the proximity of South West Fresno to clouds of industrial smoke seeping onto a smoggy backdrop, sizzling asphalt contributing to oppressive heat, the effects of Fresno’s original city plan can be seen and felt.

Racially Restrictive Covenants

One way that residential segregation was enforced was through racially restrictive covenants (RRCs) that barred non-European residents from purchasing property. Although the 1948 Supreme Court ruling in Shelley v. Kraemer rendered these covenants unenforceable; they remain in property records, reflecting a persistent legacy of segregation.

A September 2021 media release by Paul Dictos, Fresno County assessor-recorder discovered “thousands” of RRCs. He stated that RRCs “acted as the mechanism that enabled the people in authority to maintain residential segregation that effectively deprived people of color from achieving home ownership--a critical source of wealth accumulation.”

Despite the 1948 federal ruling, Dictos found deeds drafted as late as 1953. One from Old Fig included a clause excluding Black, Chinese, Japanese, Hindu, and Malay residents and their descendants, allowing only domestic employment for such individuals.

California Assembly Bill 1466, effective in 2022, now requires that RRCs be redacted from property records.

Redlining

Redlining “categorically denied access to mortgages not just to individuals but to whole neighborhoods,” a practice sanctioned by the federal government under the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) between 1933 and 1954.

The HOLC was sponsored by the federal government as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, a response to the Great Depression aimed at providing relief for people affected by the 1929 stock market crash. HOLC largely excluded minority communities from housing relief programs.

Redlining was legal and practiced until the Fair Housing act of 1968.

Highways and Urban Fragmentation

Starting in the 1950s, highway expansions further displaced and marginalized communities. Hensley cites one Board of Supervisors member who described the 99 as “Fresno's Berlin Wall.” Subsequent upgrades to Highways 168 and 180 in the 1990s facilitated eastward urban sprawl, isolating nonwhite neighborhoods further.

Later city documents referred to Shaw Avenue as “Fresno’s Mason-Dixon Line,” a dividing line that still carries social significance. The popular local saying “I don’t go south of Shaw” is using coded language that reflects these historic divisions. Whether intentional or not, the mantra has racist undertones.

Despite these physical, social, and economic barriers, Chinatown has remained and continues to be a hub of culture, history, and community resilience.

Historic Buildings, Tunnels, and Chinatown Today

Chinatown Fresno, and now the Cultural Heritage Center, have worked to preserve the neighborhood’s history through walking tours and community events.

A recent example, during the Community Land Trust Convention, participants were guided by Morgan Doizaki of Central Valley Fish Co. and June Stanfield, owner of the Pop-Up Place, which houses her barber shop, Golden Cuts, and every radical Fresnan’s favorite bookstore, Judging by the Cover.

The tour, attended by about 30 participants, highlighted the significance of multiple sites across Chinatown’s 18 blocks. Photos by Mars Santos.

Doizaki is the third generation in his family to own Central Valley Fish Co., founded in 1950 by Akira Yokomi, namesake of Yokomi Elementary School. Stanfield’s Pop-Up Place building has been in her family for decades. Both emphasized the importance of preserving these spaces as living history.

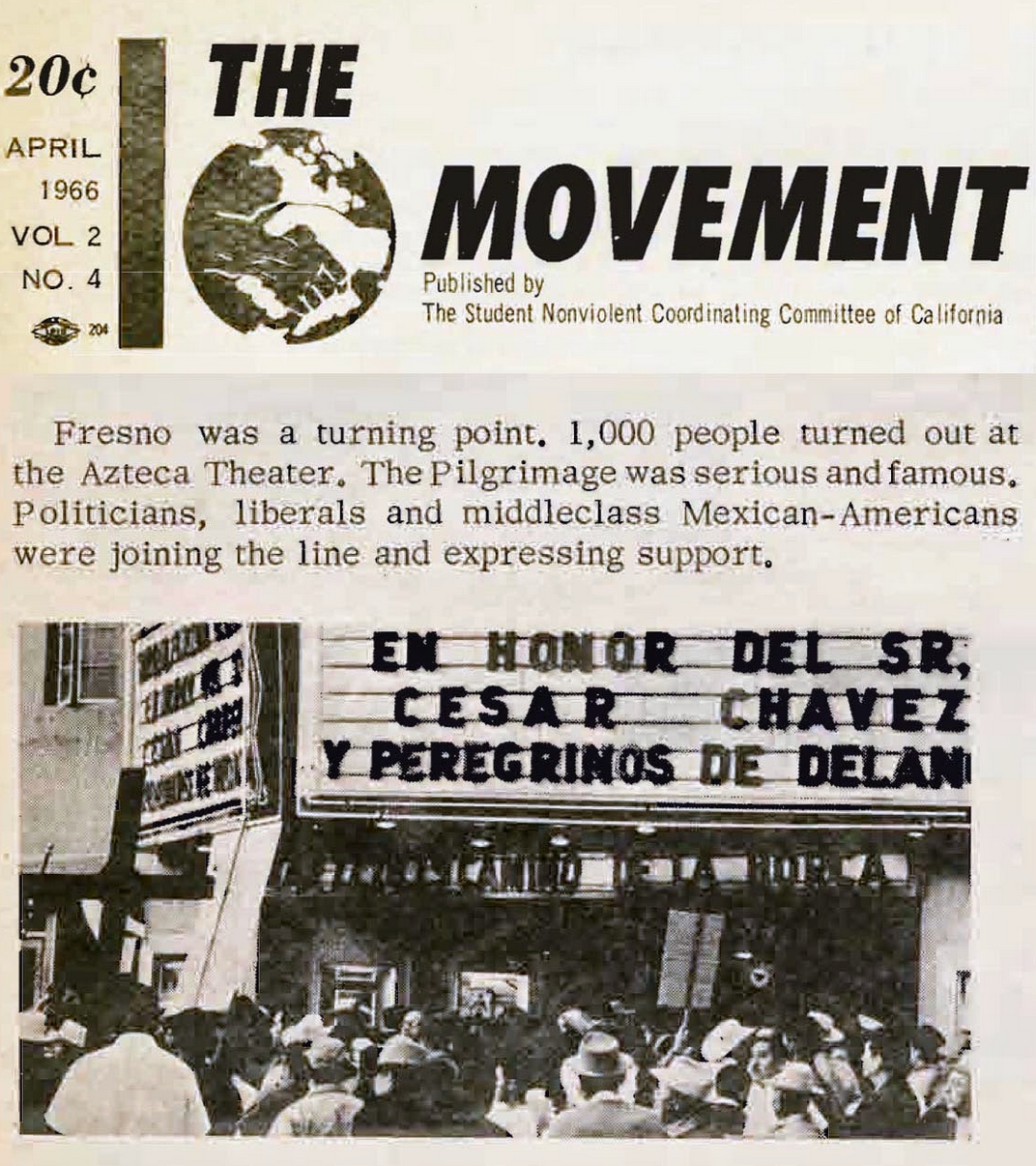

La Azteca Theater

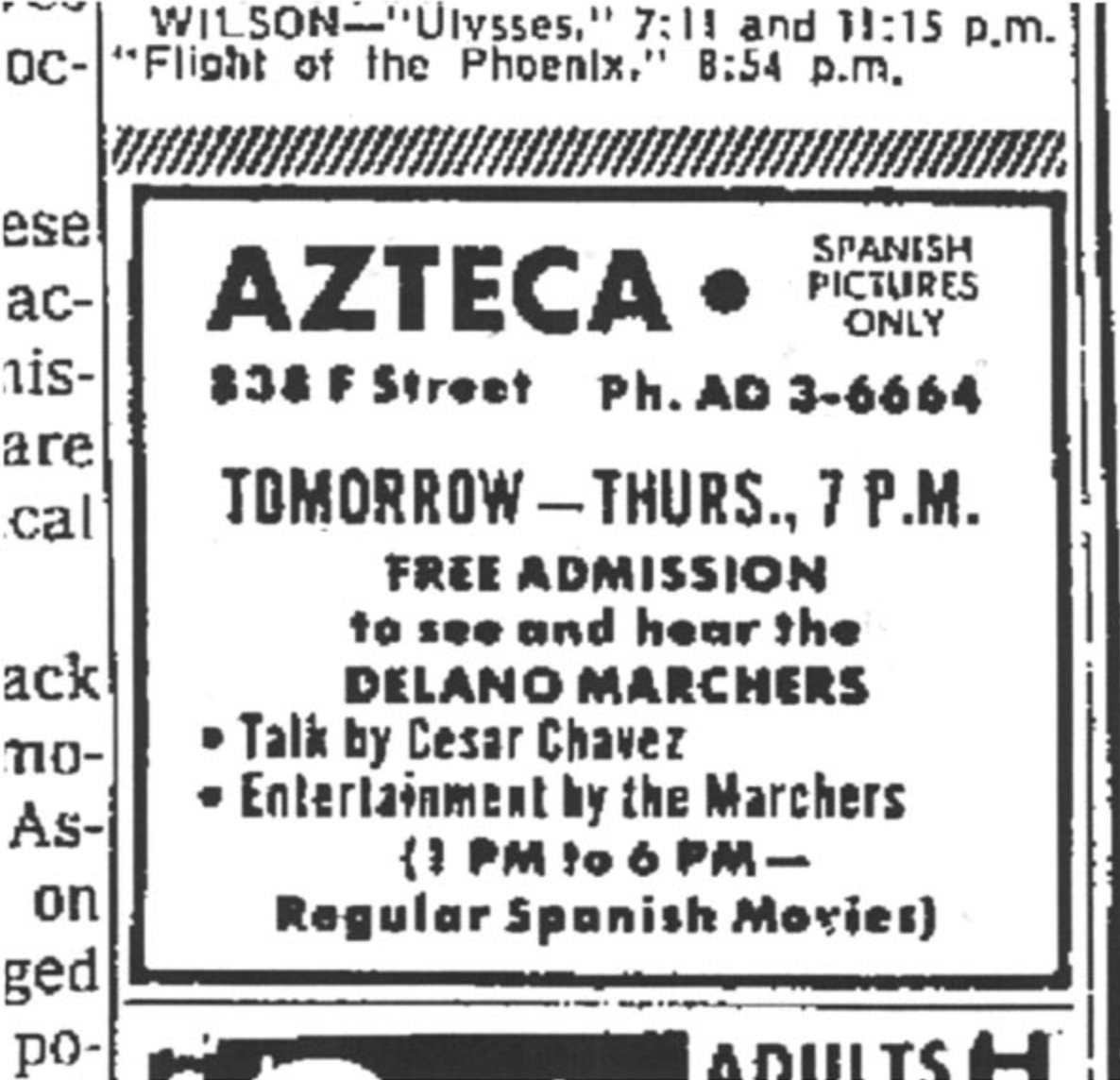

The Azteca Theater, the only Spanish-language theater in the Central Valley until 1980, served as a cornerstone for the Latine community in the mid-20th century. It remains the only building in Fresno on the National Register of Historic Places.

Archival clippings from the Fresno Bee and the Movement Newspaper documented the theater's role as a gathering point during the Delano Marches. On their 100 mile march, The Azteca was the site of a rally where Cesar Chavez gave a speech.

The Azteca Theater today (photo from Chinatown Fresno), a clipping from the Movement Newspaper April, 1966, a clipping from the Fresno Bee, 1966, The Azteca Theater today. Photos by Mars Santos.

Other historic buildings, including the recently demolished Bow On Tong building, illustrate both the richness of Chinatown’s architectural history and the threats it faces from redevelopment. Local reporting by Fresnoland noted the building was declared “unfit for rehabilitation” before demolition.

Read more about Chinatown historic buildings here.

The Future of the CHC & Chinatown

Maps shown during the Chinatown Fresno presentation compared the neighborhood before and after the California Community Redevelopment Act of 1945.

“There were so many buildings that were declared too slighted or unusable…they were supposed to be replaced with housing. And well, that may have happened around the state but it did not happen in Fresno. There was no housing built for the demolition that was done,” Jan shared.

Jan Minami of Chinatown Fresno outlined revitalization projects including business support, cultural preservation, and long-term urban planning efforts such as opening underground tunnels for tours and capping the local freeway to create green space.

The Chinatown tunnels were once used for storage and underground passage between businesses. There are also popular rumors that they were used during prohibition to transport bootleg alcohol.

The tunnel tours are under development but can't open yet due to safety issues with low-hanging pipes and other construction needs.

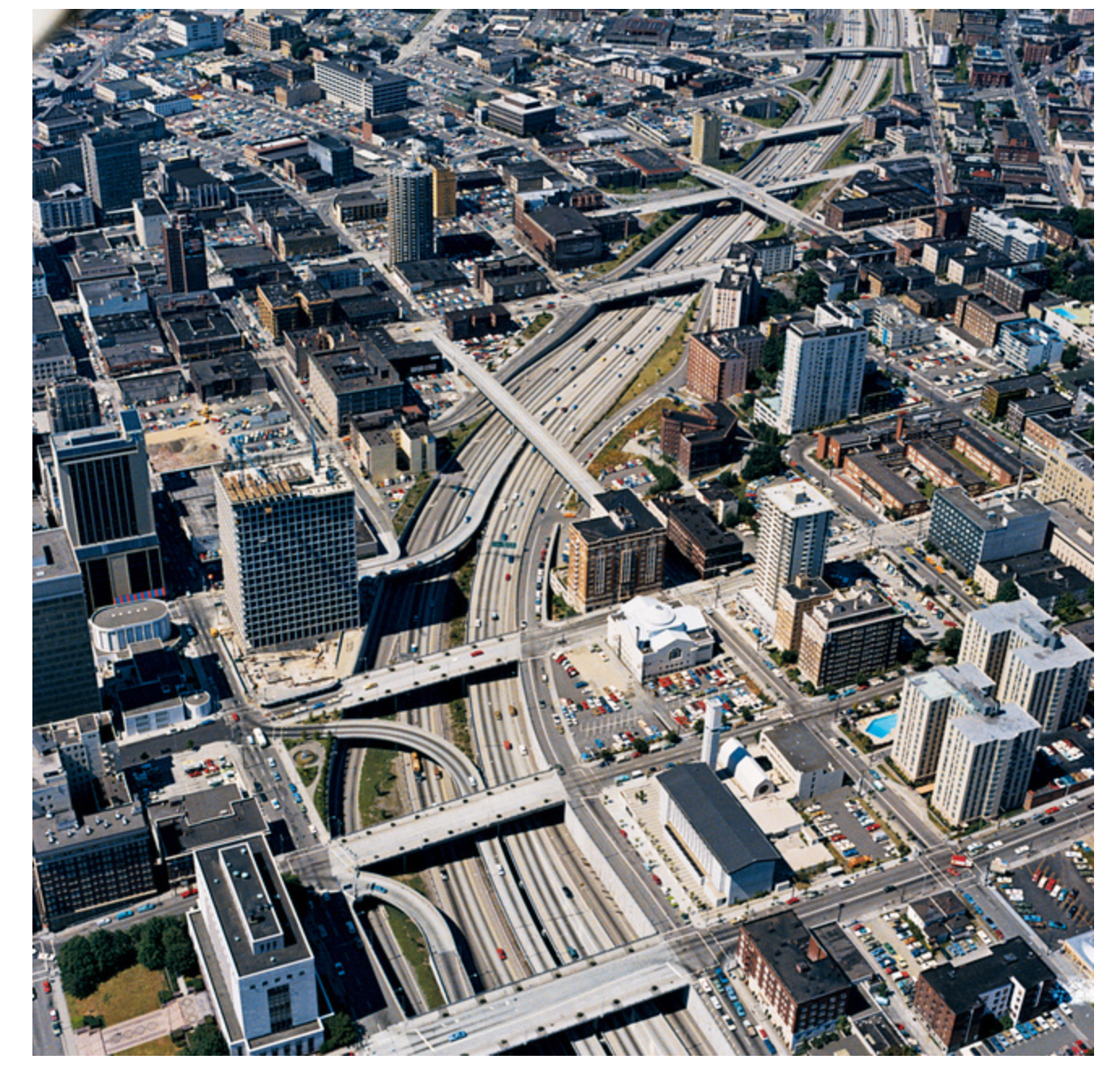

Highway caps are essentially parks built above highways. Their purpose is to reconnect neighborhoods in urban communities that were displaced to make way for federal interstate construction.

"The intent of the freeway system was to divide communities of color. So this is a legacy highway. I want to put a cap on it to reconnect the communities," Jan said.

She acknowledged that despite challenges it is possible, citing cities like Seattle who have two caps. Many others have and are in the process of building them throughout the country.

Seattle’s I-5 before and after Freeway Park was built. Freeway Park was the first highway cap park in the U.S. Construction was completed in 1976. Source: https://lidi5.org/history/

While previous grant applications for a Fresno cap study have not been successful, Jan is working with a group called Reconnecting Communities Institute, part of the Federal Department of Transportation. “I don't think it's going to happen in my lifetime, but I am prepared to charge and find any open at all,” she said.

Highway cap parks, also called lids, decks, and covers, are designed to reconnect neighborhoods displaced by federal interstate construction. Read about New York’s Plan. Video with 10 examples in the US: https://youtu.be/Bp0faVOdf2c?si=ycLCEI8bCkfL5MFx&t=219

Additional revitalization funded by the Transformative Climate Communities grant includes pedestrian lighting and tree planting.

Chinatown Present

Fresno has invested millions in downtown revitalization, with specific allocations for Chinatown. By connecting historical injustices like redlining and highway displacement to present-day challenges, these projects celebrate community resilience while fostering opportunities for cultural preservation and economic growth.

Chinatown remains a vibrant center of Fresno life, with more than 60 operating businesses including restaurants such as Ho Ho Cafe, Central Fish Co., La Elegante, Chef Paul’s Cafe, and Tamale Mama’s.

“We have the best food in town, honestly, in my opinion,” Jan said.

She shared that Chef Paul started his restaurant on a dare, turning a challenge into a storefront that continues to serve the community.

Shopping options include Judging by the Cover bookstore and Yoshi Now!/Yoshi World. The recently reopened tunnel on Tulare Avenue, directly adjacent to Chukchansi Park, provides pedestrian access directly into the heart of Chinatown.

Discover more to do in Chinatown at their website.

“We're really tapping into the most beautiful threads of Fresno. And I think a lot of those values, which are cultural values and human rights values, are leading the vision for tomorrow's Fresno,” said Pheng.

References

AGBU. (n.d.). Alex Manoogian in memoriam: Fresno home away from home. Retrieved from https://agbu.am/alex-manoogian-memoriam/fresno-home-away-home

Chinatown Fresno Foundation. (2025). Historic buildings & maps. Retrieved from https://www.chinatownfresno.org/_files/ugd/a860e7_7a020657893b4e9183f58e4b2c810a8e.pdf

Chinatown Fresno Foundation. (n.d.). Chinatown historic documents. Retrieved from

https://b4d1727c-e433-45fe-8910-8aabfbc0f8e7.filesusr.com/ugd/a860e7_ea2094c24ef54a259bd637a6a6197d01.pdf

https://www.chinatownfresno.org/_files/ugd/a860e7_4e23f6c448e44a288f24d8fdf0d7f556.pdf

https://www.chinatownfresno.org/_files/ugd/a860e7_374f04ed9328488695d728a7dae33d14.pdf

https://www.chinatownfresno.org/_files/ugd/a860e7_04883887688348a8b09c7fec7948904d.pdf

Dictos, P. (2021, September). Removing racially restrictive covenants. Fresno County Recorder. Retrieved from https://www.fresnocountyca.gov/Departments/Recorder/News-Updates/Removing-Racially-Restrictive-Covenants

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. (n.d.). Fresno case study. Retrieved from https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/fresno_case_study.pdf

Hensley, N. K. (2023). Mapping inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond. Retrieved from https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/

Los Angeles Times, & Fresno Bee. (1966). Archival clippings.

Morano, J. (2025, April). Fresno clears the way for affordable housing in Chinatown. Fresnoland. Retrieved from https://fresnoland.org/2025/04/01/fresno-clears-the-way-for-affordable-housing-in-chinatown-where-most-of-the-streets-are-already-closed/

Nelson, R. K., Winling, L., et al. (2023). Mapping inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. Digital Scholarship Lab. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining

The Atlantic. (2018, August 20). Fresno’s segregation. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/08/fresnos-segregation/567299

Valley History. (n.d.). Fresno settlement timeline. Retrieved from https://www.valleyhistory.org/fresno-settlement-timeline